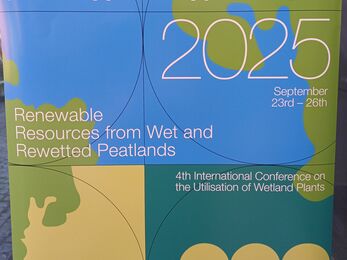

In late September, I had the pleasure of attending the Renewable Resources from Wet and Rewetted Peatlands conference. Held at Griefswald University in Germany, it brought together 380 policy makers, researchers and practitioners striving to make farming wetlands a viable option for protecting our peat.

This was the fourth such gathering and by far the largest and most inspirational. The numerous technical lectures outlined everything from mesocosm research to field-scale wildlife surveys. We were also treated with visits to exciting and inspiring projects and met those people actively working to turn wetland harvest into products at market.

I came away inspired by the passion and dedication of so many people. I'm astonished by the number of possible paludiculture products in development. They're just waiting for the right supply of raw material before they springboard into mass production. And I am admittedly, just a little daunted by the many challenges we all still face in getting to where we collectively want to be.

I want to share some of the most exciting and memorable things I saw. This was a week of being engaged and amazed at every turn.

Firstly and excitingly, The Greisfwald Mire Centre has just published a new catalogue of Paludiculture products. Download your copy.

As well as celebrating that, we were treated to the Great Paludi Show – an evening to meet product engineers and the companies investing in a wide variety of new end-uses for wetland crops. These ranged from building materials and insulation, through textiles and soft toys, to paper, drinking straws and even 3D printed products. If you would like to see your own version of a mini-paludi show then watch out for the Great Fen appearing at events in 2026. We will not only have a range of samples to explore, but we will have our own tiny house to demonstrate how wetland products could be used in the future.

Meeting the tiny-house

Speaking of the tiny-house, I was lucky enough to meet with Torsten Galke, our builder from Moor and More. We visited his workshop to see our tiny-house under construction, as well as more products under development. It was a fascinating evening where we explored in detail the challenges and opportunities in taking raw materials and turning them into a living example of products at work. Our tiny-house includes a range of materials, all of which could be grown on wet farms in future. This includes alder plywood and timber, particle boards and insulation from Typha, and sedges and reeds as acoustic baffles (and design features!).

Building bigger – the sustainable architecture exhibition

Purely by chance, we managed to secure an invite to view a sustainable architecture exhibition too – Baltic Bioregional & Paludi Prealps, wetland plants in regenerative architecture. Students and architects had explored scaling up from tiny houses to larger buildings. They were making the most of material properties to create stunning visitor centre designs using reeds, moss, birch tar pitching etc.

Boots on the ground – a visit to the typha fields

The excursion I went on was to see Neukalener Seewiesen (Fen meadows) that have been drained for agricultural use but are now rewetted. 10 hectares of typha beds have been created and have completed several cycles of harvest and regrowth. Their experience of establishing plants and the variability of yield across the site highlights how much we have still to learn to equal our understanding of growing traditional arable crops. It also highlighted for me the nuances of peatland management – every system is different and will require its own techniques for success. In this case, a system which is aquifer-fed has low levels of nutrient inputs which leads to hungry crops.

In another area we met a farming family that have turned fields which are now impossible to economically drain over to biomass production. This is initially for the local power plant but more latterly to supply a paper factory. That in turn is helping a large goods distribution company (similar to Amazon) change 100% of its packaging over to wetland paper products. The product demand in this area far outstrips supply. Another interesting aspect is that the paper process is aiming to be zero-waste. They have been using the liquid nutrients recovered during the fibre extraction process as fertiliser for other crops.

Understanding emissions

Lots of work is ongoing at different scales to understand the gas fluxes. In particular the level of methane released in rewetted field systems. This is an important part of the puzzle as it is such a potent greenhouse gas. The process of research from small-scale to large all highlights how difficult it can be to control water levels, especially during extreme weather.

Takeaways and direction of travel

So my takeaways from a week with Europe's wet farming experts are these;

· Product development is advanced. Often raw material supply is the biggest limiting factor as farmers face uncertainty over crop prices, land value and subsidies on a new type of farming.

· Crop to end-product systems can be highly successful, but only when a big industry player invests in the concept and the delivery.

· There are limitless things we could do with wetland products, but they aren’t price competitive against subsidised business as usual.